The Rule of Two is when two or more women, or those of colour, are on the hiring ‘shortlist,’ they are more likely to get hired.

“We often don’t hire the best person for the job, rather who we think would be the best person for the job.”

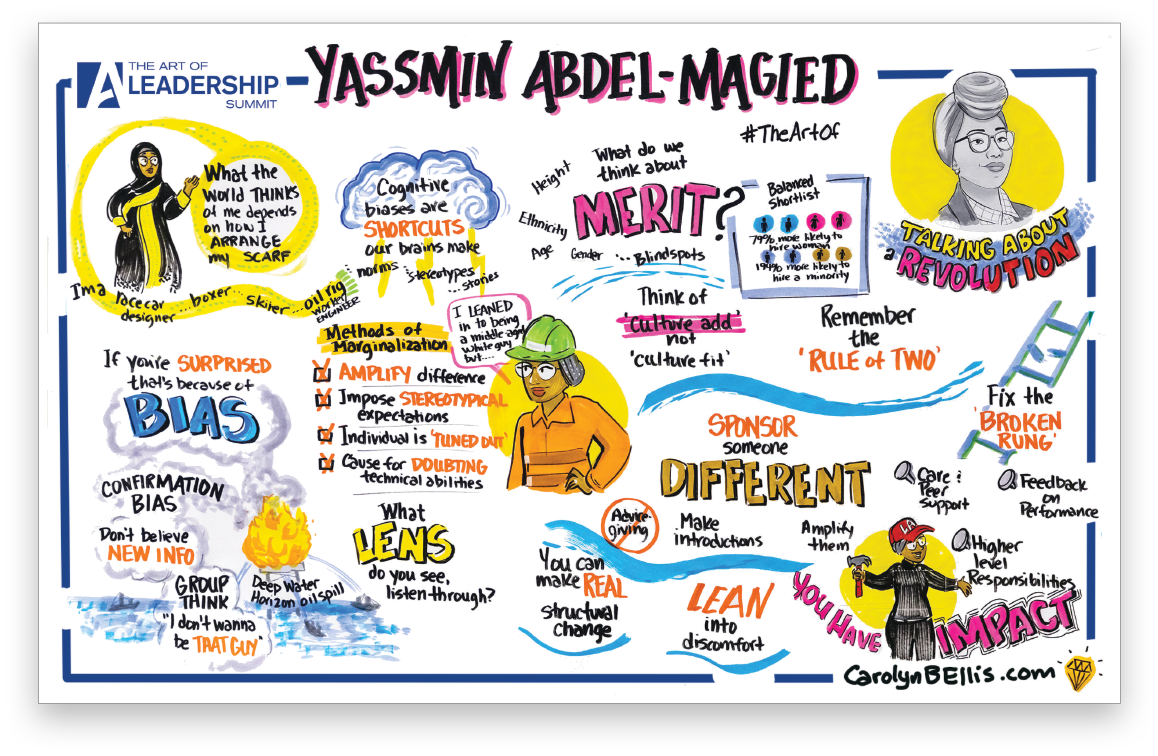

Our assumptions and the behaviours associated with them are often based on bias. Bias can be cognitive or unconscious. As individuals, we are faced with so much information that our brains make shortcuts to filter. Some of the shortcuts are useful, but some can have harmful impacts. Yassmin explained that what the world thinks of her depends on how ‘she arranges her scarf.’ Many people are surprised to learn she has been a racecar driver, boxer, skier, and oil rig worker.

Yassmin encourages us to ask, “what is the problem with bias?” Confirmation bias is when we re-interpret new information to reinforce what we already know. Groupthink is when no one in an organization speaks up, even when they know something the organization is doing is incorrect, as they do not want to ‘rock the boat.’ Yassmin uses the Deep-Water Horizon Oil Spill example to demonstrate that we can have fatal incidents if we do not tackle our biases as leaders.

Research has demonstrated that bias is faced by females in the engineering industry. The following findings have been proven:

- Difference is amplified: women in engineering are constantly reminded that they do not belong and are not ‘one of the team’.

- Imposition of stereotyped expectations: female engineers were seen as female first and engineers second. Many female workers were given ‘female’ deemed tasks such as birthday cake organizing and received no credit for tasks not part of their actual job.

- Individual is ‘tuned out’: the idea revolves around whose voice has authority and who we listen to. Women’s voices are often ignored even when they come up with a solution first. This ultimately harms the promotion of women.

- Cause for doubting technical abilities: Men are viewed as competent unless proven otherwise; while women are viewed as incompetent unless proven otherwise. Female engineers had to work harder to get to the baseline of respect their male counterparts were automatically bestowed.

Yassmin suggests that research has demonstrated that bias and corresponding actions result in women and marginalized people being found in disproportionately low numbers in senior positions. This tendency is reflected primarily through blind spots and lack of representation.

Moreover, the idea of ‘merit’ can be flawed, as the concept often reinforces our biases. “We often don’t hire the best person for the job, rather who we think would be the best person for the job.” When hiring or promoting, we must be mindful of the ‘Rule of Two.’ This rule is when two or more women, or those of colour, are on the hiring ‘shortlist,’ they are more likely to get hired. In this scenario, they avoid the ‘tyranny of being the only one.’

Finally, we are called to examine what we, as leaders, can do about bias and stereotypes. We should strive to be a leader who is a ‘culture add’ – someone who adds to the work culture, rather than a ‘culture fit.’ We must lean into discomfort and realize that we can impact our organizations with real structural change. Specifically, to fix the broken ‘rung’ on the workplace ladder, we should:

- Demonstrate care and peer support.

- Provide structured feedback on performance.

- Give women and those of colour higher level responsibilities.

- Sponsor someone outside the dominant culture by sharing our power: amplify others and make introductions.

.png)

What Did You Think?